An Examination of the Accounting Structure

Source Documents

The Journal

A journal records all entries chronologically, though in a computerized accounting system you would be able to sort by any parameter. This process is known as journalizing.

There are several different journal types; many of them are special to a company's needs. For our purposes, we will focus only on general journals and a couple of special journals.

One special journal type is known as a sales journal, though it may be called something else, depending on the company. As the title indicates, a sales journal would record the sales of a company. A typical example would look something like this:

This would be considered a special journal. It is recording only sales transactions. This data is then netted at the end of the month and transferred to the general journal.

The General Journal

In the general journal, you would record your debits and credits for every financial transaction (lefts and rights). Take a look at this sample using the earlier model of the Orion Computer Repair Company:

|

- Melody adds $50,000 capital to start her new business, Orion Computer Repair Company . - Melody pays $25,000 deposit for 10 months' rent for her new business space. - Melody obtains $7,500 credit for purchasing computer spare parts to run her new computer repair company. - Melody receives $18,000 in computer repair orders. - Melody orders $6,500 more spare computer parts, payable within 30 days. - Melody issues two checks, one for $7,500, and the other for $6,500, totaling $14,000 in order to pay off her outstanding credits from the computer part supplier store.

|

Using the above information, here is how it would play out in the general journal:

In any typical general journal, you will have a date, description, posting reference, debits, and credits. Note that the posting reference is the reference number that the entry corresponds to when it is posted to the ledger. It is blank in our example because nothing has been posted yet.

Date entry: You will notice that for many of these items, summarized here, there should be multiple dates. For example, accounts receivable's billing of the customers repairs did not correspond to the same day as when the cash was actually received. The date is the first date the transaction started. You do not need to add subsequent dates unless they carry over to another month or accounting period. For the ease of this example, we assume that everything opened and closed in the same month (September).

Description entry: The name of the account to be debited is on the first line, and the name of the account to be credited is indented.

Posting reference (PR): In this example, it is not used. However, this would be the unique reference identification that corresponds to the entry in the general ledger.

Debit: This is the amount that is debited for the indicated account.

The General Ledger

As we have seen from the general journal, we have every financial transaction the company has made recorded chronologically. Now we need to take these transactions and rewrite them again into the general ledger, or special ledgers that in turn are summarized and get posted to the general ledger. At first glance, this might seem redundant. However, every transaction that is specified chronologically in the general journal gets posted to the general ledger in its own ledger account. The general ledger is organized into many different accounts and classified by what each transaction represents.

The general ledger is the book of a company. It contains all accounts and their balances for the accounting period. The main difference between how the general journal works and how the general ledger works is that the general journal itemizes financial transactions by date, and the general ledger is a record of financial transactions by account (or summarized by account).

Using the above example of Orion Computer Repair Company, a general ledger may look something like this:

Subsidiary Ledgers

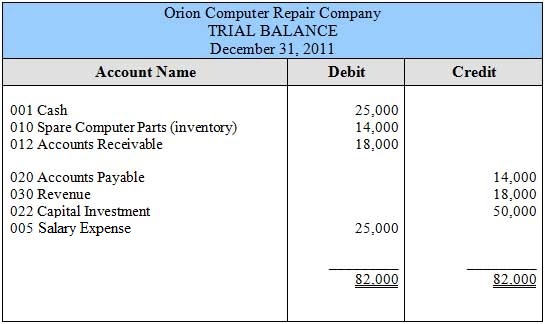

Trial Balance

The trial balance is exactly as its name suggests: It is a trial balance or test run of balancing the books. This is not a report that is seen by owners and investors; it is a report generated for the accountant, by the accountant, to determine not only where the company stands financially, but how well the books are in balance.

The trial balance is generated from the general ledger. The trial balance consolidates all this information into one convenient statement for the accountant to review and check against other financial reports, ledgers, and journals.

When the general ledger has been reviewed, balanced, totaled, and transferred to the trial balance sheet, it will look something like this:

The above trial balance sheet is oversimplified to suit our small company example. However, it does show how the overall trial balance would be balanced if everything was done properly. This is critical. If the debits and credits of a trial balance are not equal, something is amiss in the general ledger.

|

Of course, if the trial balance balances, it does not mean that it is error-free. A trial balance is still prone to the following errors:

- Debit and credit transactions are recorded in the wrong accounts

- A journal entry never made it to the general ledger or a financial transaction was never documented in the general journal

- Debit and credit transactions were recorded in reverse

If the trial balance does not balance, this means there could be errors, ranging from a simple numeric miscalculation to an improperly entered journal entry or journal posting. The best remedy against a disastrously non-balanced trial balance report is to run the report frequently and balance it frequently. In other words, try to catch the errors as quickly as they appear, instead of trying to fix everything at the year-end.